‘Nothing But A Black Puerility’

U.S. politicians are throwing temper-fits because of a federal “shutdown,” wanting to make people go without the NASA.gov website and World War II memorial access, and Disney is making films about its animated villains such as Maleficent and now also Cruella de Vil.

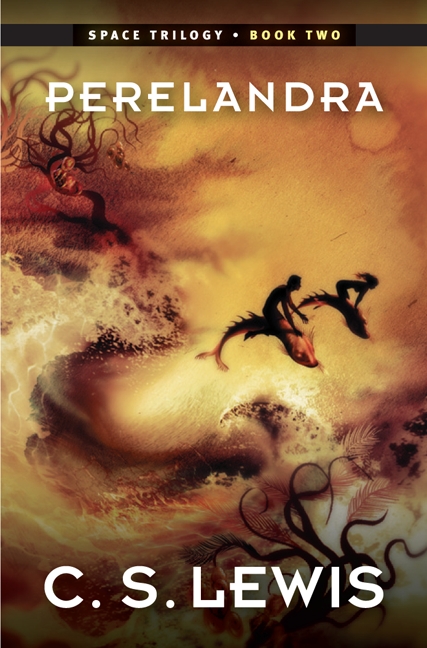

These topics actually relate, thanks to a scarily astute portion of C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra.

These topics actually relate, thanks to a scarily astute portion of C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra.

If you haven’t read at least the first two volumes of Lewis’s Ransom Trilogy (often termed the “Space Trilogy”), Perelandra follows the Godly and scholarly Dr. Elwin Ransom to the planet Perelandra (Venus). There on this watery world, Ransom encounters Venus herself, an innocent emerald Eve-like woman in a domain uncorrupted by sin — just before that corruption arrives in the form of scientist Dr. Weston.

One of the villains of the trilogy’s previous novel, Weston now shuns his former classic humanism in favor of a cosmic variety. No longer does he worship “man” (really an ideal of man in his mind); instead he gives himself over to a “life force.” Slowly Ransom concludes that this is a devil, or perhaps the Devil himself, and thus begins a grueling spiritual battle.

Or rather, the battle starts out spiritual. As this Satanic enemy wearies of engaging Ransom in debate over the green lady’s soul, he attempts startling psychological warfare. Readers to this day may be haunted by one of these ploys in the night, when Weston — hereinafter referred to as “the Un-Man” by a philosophizing Random/narrator — calls out through the dark, “Ransom.” When Ransom answers, he only says, “Nothing.” Each time Ransom replies he only says, “Nothing.” But when Ransom stays silent, the Un-Man still asks, over and over.

This brings Ransom’s slow realization about what his demonic, ultimate-evil enemy truly is.

[Ransom] taught himself to keep silent in the end: not that the torture of resisting his impulse to speak was less than the torture of response but because something within him rose up to combat the tormentor’s assurance that he must yield in the end. If the attack had been of some more violent kind it might have been easier to resist. What chilled and almost cowed him was the union of malice with something nearly childish. For temptation, for blasphemy, for a whole battery of horrors, he was in some sort prepared: but hardly for this petty, indefatigable nagging as of a nasty little boy at a preparatory school. Indeed no imagined horror could have surpassed the sense which grew within him as the slow hours passed, that this creature was, by all human standards, inside out—its heart on the surface and its shallowness at the heart. On the surface, great designs and an antagonism to Heaven which involved the fate of worlds: but deep within, when every veil had been pierced, was there, after all, nothing but a black puerility, an aimless empty spitefulness content to sate itself with the tiniest cruelties, as love does not disdain the smallest kindness?

This may explain political temper-tantrums and show the absurdity of the Disney movies.

Political enemies

If you’re a spiritual sister or brother from another cultural “mother,” you may offer another example; mine may suffer at least a selection bias, at least based on yesterday’s headlines.

Several articles covered the federal “shutdown,” because of which the American executive branch shut down some websites (including NASA.gov) and even closed attractions for no apparent reason. One incident occurred at the World War II memorial in Washington, D.C., a memorial that is outdoors, easily accessed, and which would require more federal costs to shut down than to leave alone. In short, that closure certainly appeared designed to prove to American citizens that they must suffer more than usual under this “shutdown.” The executive branch says: Fine, you want to shut down government? Then people can take THIS.

I would take all this back if evidence released that somehow, authorities who bring in more staff to close an always-open outdoor landmark somehow need less government resources than when it’s business as usual. But right now it looks like “an aimless empty spitefulness.”

Ransom’s thoughts on his enemy are so true: some enemies, in politics and any other field, are morally inside-out. On the surface they appear deep. Inside they’re infantile and nasty.

Disney enemies

This is why attempts to explore backstories of some fictional villains seem so absurd. For now let’s bypass the fact that these are likely motivated only by name recognition; movie-makers want to cut through the “fog” of other media especially since the internet arrived. Who cares to know “the events that hardened [Maleficent’s] heart and drove her to curse young Princess Aurora,” as this IMDB description says? Who needs a story focusing solely on Cruella de Vil from 101 Dalmatians? If there’s any deep thought going on here, it seems of the worst sort: that we must explore evil, explain it, give villains a backstory, every time.

Such explorations do not always add “realism” or nuance. If anything they provide escapist fantasies, taking us away from this fact: that some evils, when you look under their skins, are supported by the skeletal structure of absolutely nothing but “black puerility” and spite.

Tell me about it. At best, exploring the villain’s motivations makes them more frightening 50% of the time– but I think the ratio is more like 10% more frightening, 90% lame/too sympathetic.

I dunno about this. In the human world, pretty much everyone views himself as the hero of his own story. People don’t sin because they want to be evil; they sin because they want to achieve some aim they deem to be good or logical, or at least worthwhile. The motive may be difficult to perceive, but it’s usually there. If we’re content to be entertained by two-dimensional, mustache-twirling villains whom we can hate with our whole hearts whilst puffing ourselves up because “we’re not like them,” then we become vulnerable to the complacent self-delusion that we’re incapable of villainy ourselves. An exploration of Maleficent’s descent into evil should (if done well) hold up a mirror whereby we can examine our own motivations and extrapolate out from our own sinful proclivities.

Thus my ending disclaimer:

In other words: Sometimes they do. But not always.

Not always. The example that springs to mind is St Augustine, who as a teenager stole all his neighbour’s pears – not because he wanted them (he fed them to the pigs!) but for sheer badness.

Absolutely! Villains (like Saints) are people ‘just like us’.

Indeed. And sadly, even redeemed saints all know how spiteful we can be in our worst moments — for we remember and still struggle with such wretchedness.

I have yet to clearly balance the perspective of this article with what Austin posted above. On one side, evil people are complex, because what else could it be when an eternal soul turns from it’s own purpose? On the other, capital E Evil is, at its center, simple. That’s not a paradox, precisely, but it is a bit confusing.

I think as Austin wrote above, both truths apply. People do begin as more complex, and may remain complex, as they begin their slow descent into evil — unless the power of Christ reveals His grace to them that is worth far more than any of sin’s pleasures. And yet as you said, “pure” evil is simple and infantile, the epitome of self-devouring and spite. The difference is not of motive in different people, but time. Surely and sadly, all who end up outside of Christ’s grace will degererate into just this kind of behavior. That’s what makes hints of it now even more frightening.

With that nuanced-to-infantile progression of evil in mind, it makes perfect sense for Disney et al. to create complex origin stories for their famously one-note, maniacally-cackling, world-domination-seeking, causing-pain-for-the-evilz villains. Though these tyrants started out by striving for what in their eyes seemed good at the time, they ended up as nothing but black puerilities.

Weston was empty at this point in his life. But he had not started out like this – he become this way. His course of life was not a result of empty pettiness – the empty pettiness was a result of being literally possessed by evil spiritual forces. Which was a result of his grandiose ideas and dabbling in dangerous stuff. He was a normal human who had given himself over to spiritual forces and was now possessed by them. Which is hopefully not the case with the politicians… (I know we all give ourselves over to sin, but that’s different. He wasn’t just a sinner – he was literally possessed)

I’ll add something which may or may not cloud the issue. I think Disney is doing what they realize will sell. I think it was Wicked, the story about the previously designated Wicked Witch of the West, killed by Dorothy, that delved into her backstory and showed how she came to be that evil person. Because of it’s success, I’m guessing a “me too” event began. I could be wrong, but I think corporations tend to be more about dollars and cents than they are morals and sense. 😉

Becky

True. It’s based purely on name recognition and the “trendiness” of the “how the headliner villain Came to Be” storylines. Yet some scriptwriter, even if tasked to do it by the corporate folks, must at least give an effort to developing a story, however shallow, with the themes of good-person-becomes-evil. Here there is a chance of doing something new, or else doing too much on the side of “evil people are more complex and have reasons for what they do,” and not enough of the coequal truth that: “Evil is just plain bad! You don’t cotton to it. You’ve got to smack iot on the nose with the rolled-up newspaper of goodness! Bad dog! Bad dog!”