Seven More Lies Christians Believe About ‘The Shack’

Does The Shack teach that God is a woman or that all humans go to Heaven? Is the book more “real” or authentic than other Christian fiction? Has William Paul Young’s bestselling book, which is now also a film adaptation, been wrongly treated by critics and pastors?

Short answer to all of these triune questions: yes. But perhaps not in the ways you think.

In The Shack’s own spirit of “not in the ways you think,” let’s explore seven more lies Christians believe about The Shack, asking and answering these questions as fans of both biblical faith and fantastical stories. First, make sure you start with the first six lies here.

Lie 7: ‘The Shack has a single false/true view.’ No, it’s complicated.

Young continues to identify as the sole author of The Shack. The book’s actual authorship is a bit more complicated. There was even a lawsuit about it. In the end, author and publisher Wayne Jacobsen also speaks as the book’s coauthor (with Brad Cummings), stating flatly, “Paul isn’t the only author of this story.”1 So the book was written/edited by committee, and only later picked up for larger distribution by Hachette Book Group.2

Young continues to identify as the sole author of The Shack. The book’s actual authorship is a bit more complicated. There was even a lawsuit about it. In the end, author and publisher Wayne Jacobsen also speaks as the book’s coauthor (with Brad Cummings), stating flatly, “Paul isn’t the only author of this story.”1 So the book was written/edited by committee, and only later picked up for larger distribution by Hachette Book Group.2

This joint authorship, like with some written-by-committee blockbuster movies, may help explain some of the clashing tones and ideas within the story. It helps explain why The Shack sounds so biblical at one moment, as demonstrated in part 1 and as shown here:

- “Creation and history are about Jesus. He is the very center of our purpose, and in him we [I would add: that is, redeemed Christians] are now fully human.”3

- “There has never been a question that what I [God] wanted from the beginning, I will get.”4 Here Young, et. al. implicitly denies the false “open theism” notion, that not even God can foresee future events and is operating with some element of risk.

- The Triune God doesn’t need others (including human beings) to be fulfilled. Instead, God lacks nothing, being already “love” among His Persons.5

… But then The Shack offers clashing notions such as that although God always gets what s(he) wants, s(he) either does want to allow evil and suffering for good reasons,6 and/or is helpless when an evildoer abducts and kills a child.7

Moreover, if one author (Jacobsen) says he does reject universalism, but another author (Young) very clearly accepts it, that puts a crucial religious divide at the heart of the story. Unlike the unified God the authors wish to explore, this trinity of human authors is not very well unified. Thus the book’s narrative voice(s) become unreliable and self-conflicting.

Lie 8: ‘The Shack is better fiction.’ It’s often poorly written.

Some fans of The Shack have praised the book as if it is better than most evangelical fare. I began the book at least hoping for good writing. But soon I sensed The Great Sappiness:

[Mack] hit hard, back of the head first, and skidded to a heap at the base of the shimmering tree, which seemed to stand over him with a smug look mixed with disgust and not a little disappointment.8

Yes, Mack wanted more, and he was about to get much more than he bargained for.9

Summer wildflowers began to color the borders of the trail and the forest as far as he could see. Robins and finches darted after one another among the trees. Squirrels and chipmunks occasionally crossed the path … [deer, flowers, fragrances, anything except city-based imagery that the Bible also favors to describe paradise (Rev. 21), and then …] The dilapidated shack had been replaced by a sturdy and beautifully constructed log cabin, now standing directly between him and the lake, which he could see just above the rooftop. … Smoke was lazily wending its way from the chimney into the late-afternoon sky … A walkway had been built to and around the front porch, bordered by a small white picket fence.10

This scene is identical to a Thomas Kinkade painting; The Shack has become The Cottage™.

This scene is identical to a Thomas Kinkade painting; The Shack has become The Cottage™.

But The Great Sappiness isn’t limited to the settings. Mack’s daughter Missy acts and speaks like an iconic perfect little girl, the kind seen in Sherwood Pictures movies (complete with tragedy like her Courageous counterpart). Ideas also smack of reality-denying sentiment:

- Forgiveness is not a moral exchange between human beings; it is primarily an emotion. Yet somehow you can still feel angry even after “forgiving” someone. Forgiveness does not even have real effects to restore relationship between people.11

- Papa says, “There is power in what my children declare,” a nod to prosperity gospel and/or American-Christian dream teaching.12

- “It is a tree of life, Mack, growing in the garden of your heart.”13

- Also, ten points from Young for severely dated The Matrix references.14

Some may object: wait, isn’t The Shack more like Christian classics such as “The Chronicles of Narnia” that more fully engage deeper ideas and push imagination? Unfortunately, no, The Shack is not like the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, George MacDonald and others Young credits for “creative stimulation.”15 Christians may like to drop these names for credit by self-association. But we often do not see why these classic works last while others fade. For example, Lewis believed in the value of old poets and myths to teach us, including the “true myth” of the Bible. Young gets this exactly backward: it is he who will instruct the old myths. He will put them in their place. And alas, despite all the story’s pleas for doctrinal humility, this is perhaps the greatest form of religious arrogance hidden in The Shack.

Therefore, I doubt the book (and movie) will have much cultural impact beyond Christian and nominally Christian audiences. It offers familiar images and tropes of the most shallow kinds of Christian fiction, only turned up to 11, yet offers even less biblical truth than those.

Lie 9: ‘The Shack deals honestly with evil and pain.’ It denies them.

The Shack’s preference for sentimentalism is clearest when it seeks to address the themes of evil and suffering. This is no false expectation by doctrine police, but the book’s own mission. Its cover slogan is, “When Tragedy Confronts Eternity.” The back cover promises:

The Shack’s preference for sentimentalism is clearest when it seeks to address the themes of evil and suffering. This is no false expectation by doctrine police, but the book’s own mission. Its cover slogan is, “When Tragedy Confronts Eternity.” The back cover promises:

In a world where religion seems to grow increasingly irrelevant The Shack wrestles with the timeless question: “Where is God in a world so filled with unspeakable pain?”

The Shack does not wrestle. It merely gives this question a mere slap on the wrist with a lace-trimmed glove.

Its ill treatment begins with a writing style that hovers over characters and does not go inside. We do not truly feel Mack’s sadness. Verbiage adds distance, not intimacy. His emotions even have their own distinct title, like an album: The Great Sadness.

Mack’s denial of emotions is also bashed into our heads with sentences like, “With every effort he could muster, he kept himself from falling back into this black hole of emotions.”16 (Really? So not confronting these negative emotions is bad? Or could this be a bit clearer?)

Perhaps worst of all: Any real impact of these terrible events—that Mack’s daughter is abducted, presumably raped, and murdered—is blunted by the story’s gross assurances: it’s not as bad as we think, God manifested to Missy to lessen her terror, and spoke to her heart, and Missy even prayed right then for her father’s peace.17 Here and elsewhere, The Shack refuses to show human evil and suffering closer to their realistic worst. Even as the authors teach us that Mack’s denial of emotions = bad, weeping = good, they deny us real reasons to weep. This is The Shack at its most sticky and saccharine, and I felt offended by its entire implication.

Even worse, all of a sudden, this one encounter with “God” fulfills all eschatological hope in Mack’s soul. “His constant companion, The Great Sadness, was gone. … The Great Sadness would not be part of his identity any longer.”18 “The Great Sadness is gone …”19 To be sure, happy endings should occur in books. But not like this, and not if you promise your book will skip past all that irrelevancy of corny religion and really dig its hands into the world’s crap. In reality, God does not heal our hearts so quickly. To claim otherwise is to tell a great lie.

What then of existing biblical, historical, and/or philosophical responses to the problem of evil and suffering? The Shack does not care for them. It does not let previous Christian teaching even speak for itself. Bad “seminary” answers and book-learnin’ lurks in the background, barely even allowed to fling a black cape versus the supposedly better answers Mack is taught in the titular shack. Perhaps the reader can therefore imagine their own villain back there (such as that one pastor/ministry/belief the reader especially despises). But this is not the role of a story that gets real and represents its antagonism brutally. It is the role of propaganda.

Lie 10: ‘The Shack doesn’t really preach that God is like a woman.’ In fact, it really does preach this, but not in the way you think.

Critics like to raise a ruckus over The Shack’s portrayal of God the Father, and God the Holy Spirit, as semi-incarnate non-white women. In response, fans defend the book. Coauthor Jacobsen is among them and un-subtly suggests that “for some [the criticism] may have been more about ‘black’ than “woman’ …” Nonsense. Serious criticism has nothing to do with “God’s” skin tone, but with the notion that the other two Persons of the Triune God are in the habit of imitating Jesus and semi-incarnating as shape-shifting humanoids. 20 But all of Scripture, the true myth Young disregards, shows that the Incarnation is Jesus-specific. “He is the very image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation.”21

Young, Jacobsen, and others insist the book doesn’t really teach God is a human woman. After all, Papa later shape-shifts into a human male one day because, as (s)he explains, “This morning you’re going to need a father.”22 So the defense goes: That’s just how God needed to be, to help Mack bypass his own stigmas of God and his human father.

But why is that necessary? The Shack doesn’t explain. Nor can it bypass the fact that Mack does not relate as easily to “Papa” (the Father) or “Sarayu” (the Holy Spirit) but rather to the male person of Jesus, similar to the Bible itself. God has already recognized our need for intimacy with Him, despite His initial holy distance from we his enemies. But He does not respond with female “imagery,” but by preserving His self-identification using exclusively male pronouns23 and dwelling with us as Jesus—who is neither Father nor Mother but our Brother.24

However, The Shack’s main problem isn’t the female characters. The author(s) have deeper intent: to show that there are “womanly” virtues, such as relationships, that are closer to God’s nature than “male” practices, such as power. The book doesn’t deny that women sin. But it does suggest that women finding hope apart from God and in human relationships is at least closer to God’s ideal,25 while men usually behave worse:

“The world in many ways would be a much calmer and gentler place if women ruled. There would have been far fewer children sacrificed to the gods of greed and power.”26

Mack shook his head and looked up. “So, I don’t really understand reconciliation and I’m really scared of emotions. Is that about it?”

Papa didn’t answer immediately but shook her head as she turned and walked away in the direction of the kitchen. Mack overhead her grunt and mutter, as if only to herself, “Men! Such idiots sometimes.”27

This alone might not be bad. But the story offers no female characters who struggle with sin. Women are cast as God-characters or else human icons, such as Mack’s wife, Nan, who rarely speaks, or Missy, who only speaks angelic-evangelical-movie-daughterese.

This alone might not be bad. But the story offers no female characters who struggle with sin. Women are cast as God-characters or else human icons, such as Mack’s wife, Nan, who rarely speaks, or Missy, who only speaks angelic-evangelical-movie-daughterese.

Moreover, the story’s very notion of some virtues as “male” and others as “female” seem sexist even for a secular reader. Why can’t men be natural nurturers? Why can’t women be powerful and yet not sin? Is it evil for a woman to feel anger against an abuser? Must a woman or a man be forced into fake “forgiveness” of an offender who has violated her or committed violence on her? What if we gender-reversed The Shack in which a woman character confronts her rapist in a paradise vision and, despite having no felt or seen evidence that he has repented or that justice has been done, is compelled to “forgive” him?28

The Shack simply doesn’t engage with a rather mind-blowing notion: God, not human beings, can hold all the virtues. He is the embodiment of each one, while on our own, humans reflect these in limited or even corrupted ways. The Shack simply ignores biblical portrayals of Him as both mercy and vengeance, love and hatred (eternally against sin and unrepentant sinners), distant/unapproachable and up close/personal (Emmanuel, God with us).

Lie 11: ‘The Shack doesn’t promote universalism.’ No. It does.

Universalism is the false belief that God will somehow, eventually, redeem all individual humans and will not need to torment some humans for eternity.29

The Shack coauthor Jacobsen denies he is a universalist in very plain and helpful terms:

Perhaps the most problematic accusation is that The Shack promotes universalism, the belief that everyone gets salvation in the end. Some who advance this idea quote from Paul Young’s paper for a think tank written before The Shack. Even today he describes himself as a “hopeful universalist”. … When [Young] first sent me the manuscript, universalism was a significant component in the resolution of that story. When he asked for my help in publishing the book, I told him I wouldn’t work on it if [universalism] was his answer to human suffering. I didn’t agree with it and thought it would hamper efforts to reach the audience that would most benefit from the book. 30

To his credit, Jacobsen contends a more-biblical view of eternal punishment:

I don’t have to figure it all out, but trust it to the God I know. However, nothing Jesus, Paul, or John said points me to the conclusion that everyone receives salvation. In fact they warn of significant consequences in the age beyond for refusing God’s love in this one. I do believe God’s love is universal and his desire is for everyone to be saved, but that transaction involves a response from us.31

But Young is absolutely, in no equivocal terms, a universalist, and equally boldly states:

Are you suggesting that everyone is saved? That you believe in universal salvation?

That is exactly what I am saying!

Here’s the truth: every person who has ever been conceived was included in the death, burial, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus.32

Biblical Christians ought to respond in sober horror and repeat the words of the apostle Paul: “But even if we or an angel from heaven should preach to you a gospel contrary to the one we preached to you, let him be accursed.”33

But if Jacobsen denies universalism and Young affirms it, what is actually in The Shack?

In a word: universalism.

Unfortunately, The Shack must answer for itself without helpful (and contradictory) input from behind the scenes. And by itself the story does support the heresy of universalism.

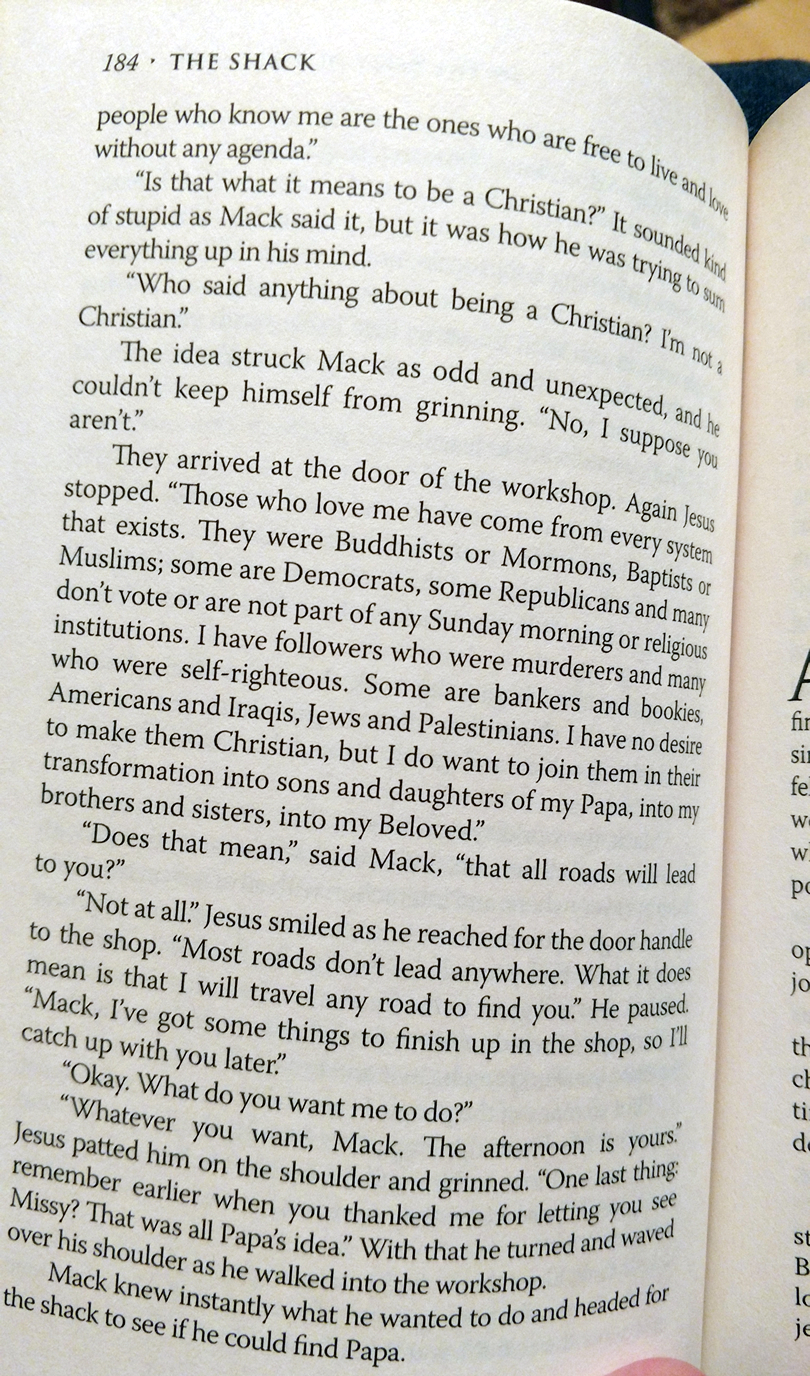

However, it’s clear from what we read that at least two authors wanted to have the story go both ways. Ultimately they seem to have settled on a political compromise. “Jesus” tells a surprised Mack (Mack spends a lot of time surprised), “Who said anything about being a Christian? I’m not a Christian,” as if this proves anything. To The Shack’s credit, he then offers a list of various religions and sins previously practiced by his followers. But then:

“I have no desire to make them Christian, but I do want to join them in their transformation into sons and daughters of my Papa, into my brothers and sisters, into my Beloved.”

“Does that mean,” said Mack, “that all roads will lead to you?”

“Not at all.” Jesus smiled as he reached for the door handle to the shop. “Most roads don’t lead anywhere. What it does mean is that I will travel any road to find you.”34

Again, The Shack is not simply fiction. One can’t resort to that rebuttal. It is a sermon, with “said Mack” and other attributions inserted to make it dialogue. The author(s) want you to adopt this belief. And this belief is universalism. No, all roads won’t lead to Jesus, and Jesus has imposed limits on His own grace (what they are is up for debate), and most roads also won’t lead simply to nothing. Many will lead to Hell, the place God prepared for everlasting torment for the devil and his angels,35 and for unrepentant human rebels. If Christians write stories like this about where other religious “roads” lead, and do not care to mention the threat of God’s wrath, they are complicit in universalism. They are hurting and hating, not loving, their neighbors by allowing and promoting such a false teaching.

What I say next, I say carefully but firmly: Damn it to hell. May God grant these false teachers repentance, so that someday in the New Earth we can together laugh about all this.

Lie 12: ‘If you enjoyed The Shack, you’re a bad Christian.’ Tastes vary.

However: all of this does not mean all fans of The Shack should necessarily feel guilty!

However: all of this does not mean all fans of The Shack should necessarily feel guilty!

Some critics of The Shack may imply that all its fans are compromisers or universalists. This is simply not the case. After all, I read the book. I’m not a heretic or a universalist. If you read the book, and you know that you’re not, then you’re not. Let no one tell you otherwise.

As I concluded in lie 6, you may feel very helped by the book. If so, great. Thank God for that. He can indeed use anything to work His will. Even false teaching. Even cancer.

You don’t need to throw away or burn your copy of The Shack.

However, please also consider this wisdom from Shannon McDermott:

Human feelings, no matter how spiritual they may seem, are not incontrovertible proof of God’s work; God’s work is not necessarily a seal of approval on His instruments. Maybe God has used The Shack, as people say, but you know, He used Pharaoh, too.

That The Shack makes you feel (correctly) that God is love doesn’t mean that it isn’t wrong in other respects; neither does it make significant errors all right. And it’s not enough to feel rightly about God; we need to think rightly about Him, too. Even the feeling that God is love, without any feeling that He is also majestic and terrifyingly holy, leaves us stranded a long way from home.

Also keep in mind that Christians’ tastes will vary. Even apart from The Shack’s overall bad theology, I did not like the book. Many others will feel the same. But I can certainly see its appeal to Christians who’ve struggled with legalistic upbringings. If you’ve been starved for the image and themes of a loving, embracing God, naturally this book will meet that need—at least at first. But go “further up and further in.” Chase the stream to the Bible’s real truth of our perfectly loving and perfectly just King, who shows true mercy and justice alike.

Lie 13: ‘You defeat The Shack fans only by preaching.’ Wrong.

Finally, if you’re a doctrine-wonk like I am, and kind of like to pick on The Shack and other false teaching, may I urge you: chill out a bit. Mind your place. Literally, mind your place.

Imagine being in church, hearing a sermon error, and standing up to disagree. That’s rude.

Now imagine walking into a library meeting room. Here, several people are reading a book and discussing it. You ignore the circle, the chairs, the cookies. You bring in a lectern and portable speaker. You set it up, and commence to preach. Is this appropriate? No. It’s rude!

Many (not all) critics of The Shack are right to engage with the book as if it’s a sermon, because it is. However, they are wrong to try to engage with the book only as preachers.

If people are sitting around reading or discussing a book, then this is a book club. You can’t be preacher today. You must first be a human being in a book club. So follow the book club rules. That means you read the book (always a plus) and first, listen. Do your best to make people feel you are listening. Listen not only to the book but to its fans. Find the book’s good points, if you can. And always emphasize with people’s positive responses, while also acknowledging that God can use anything, even lies and cancer, to draw people to Himself.

Share your feelings too. Don’t be the clichéd Bad Male who Can’t Connect with His Feelings and That’s Bad. After all, when you only talk in “facts,” that leaves a legitimate opening for people to accuse you of simply “fearing” other ideas.36

On the way, actually engage the book—really engage with it. I commend the “popologetics” method by Ted Turnau, which I have occasionally followed in this two-part article:

- What’s the story?

- What kind of world are we exploring?

- What is good, true, and beautiful about this story-world?

- What is bad, false, and ugly about this story-world, denying us the story’s promises?

- How does the actual Gospel of Jesus Christ fulfill good promises the story can’t keep?

Point 4 is especially valuable, because The Shack values its own sermons over story, offers conflicting “truths” as well as mainly sentimental and fleeting beauties, at best flirts with damnable and false teaching, and violates God’s true love and justice (which are far more fulfilling). Before we even go to the Bible to compare The Shack with God’s own revelation, we find The Shack simply cannot fulfill its own promises to offer a better story about Him.

- Who’s Afraid of The Big, Bad Shack?, Wayne Jacobsen, undated. In part 1, I remarked on Jacobsen’s difficulty in this article to avoid attacking straw men. He fails to discuss sincere criticisms of the book he helped write. ↩

- Oddly enough, at least my copy of The Shack somewhat hides Jacobsen’s role. His and Cummings’ names do not appear on the front and back covers; they only get credit in an inside front page. The Library of Congress catalog information page only shows that the book is “Copyright © 2007 by William P. Young.” Strangely, Jacobsen’s name also appears in the endorsements page, as if he himself didn’t also help rewrite the book (a role Young concedes on page 251). It’s a very strange treatment for a coauthor. ↩

- The Shack, 194. ↩

- Ibid, 194. ↩

- Ibid, 203. ↩

- Ibid, 127. ↩

- Ibid, 167. Christians may certainly disagree on why a good God allows suffering. But Young in The Shack doesn’t seem interested in the fact that this discussion has been going on longer than yesterday. ↩

- Ibid, 19. As Fred Sanders remarked in the pseudo-parody “literary snob” portion of his four reviews of The Shack: “Take a moment right now, reader, to see if you can arrange your face into an expression that communicates smugness mixed with disgust and disappointment. You will find it ‘not a little’ impossible, and you have greater expressive range than trees.” ↩

- Ibid, 68. ↩

- Ibid, 82-83. ↩

- Ibid, 227-229. ↩

- Ibid, 229. ↩

- Ibid, 236. I admit, I groaned aloud at this one. But it’s redeemable if you say it in the voice of The Tick. ↩

- Ibid, 126. ↩

- Ibid, 252. ↩

- Ibid, 85. ↩

- Ibid, 175. ↩

- Ibid, 172. ↩

- Ibid, 249. ↩

- If anything, The Shack dabbles in clichéd racial images, although with good intentions. It presents “Papa” as one of the most magical of “magical Negro” stereotypes, complete with lines such as “Child … you ain’t heard nuthin’ yet.” (Ibid, 205). ↩

- Colossians 1:15, emphases added. ↩

- The Shack, 222. ↩

- As Brian Godawa remarks, “I find it particularly revealing that in our culture that demands we accept the self-designated gender of all persons, this movie then denies that same respect to God by NOT accepting his self-designated gender (again, being judge over God). If we do not accept a man who chooses to be called female, we are a bigot, but we are allowed to deny God’s choice to be called by male pronouns?” ↩

- Hebrews 2:11-13. ↩

- The Shack, 149. ↩

- Ibid, 149-150. ↩

- Ibid, 194. ↩

- Thanks also to the shape-shifting, these portions of The Shack made me suspect that soon the whole jig would be up and someone would pull Captain Sisko and his crew out of the virtual reality. ↩

- Some other beliefs are cousins to universalism, and hold that God will save some people who didn’t repent. ↩

- Who’s Afraid of The Big, Bad Shack?, Wayne Jacobsen, undated. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- William Paul Young, Lies We Believe About God, quoted in What Does The Shack Really Teach? “Lies We Believe About God” Tells Us, Tim Challies, March 9, 2017. ↩

- Galatians 1:8. ↩

- The Shack, 184. ↩

- Matt. 25:41, among many other passages. The devil and his angels are never even mentioned in The Shack. ↩

- This is Jacobsen’s go-to defense. ↩

OTOH, there is a tradition of celebrating the feminine aspects of God, but it’s Jewish. Also, the question of gender doesn’t have to be either/or. It could be both/neither.

But there’s always the question of perception: would a culture whose ideas of legitimate power were tied up in masculinity take moral commands seriously from a goddess? “Papa’s” argument has merit on that front.

The Holy Spirit is sometimes referred to with a female pronoun, but people get way off into the weeds about it. Like you said, God embodies all virtues perfectly, and we only reflect portions of him to varying degrees.

I’ve never struggled with jealousy over other authors’ success. I’m glad Young’s had financial success with The Shack. What DOES bother me greatly is his audience’s acceptance of errant beliefs, driven by the innate human desire for comfort. It also bothers me that The Shack is just another work people can use to build a case that fiction SHOULD be a sermon (because, well, heck, it’s sold over 10 million copies, it must be good!).

I’m trying to be careful in this next paragraph, and to keep an objective perspective. I also don’t want to be self-promoting, but to make the point I want to make, I have to talk briefly of my own experience publishing and getting feedback from readers. My debut novel, Cain, attempts to honestly explore the issue of human suffering and why God allows terrible things (like Abel’s murder) to happen. Yet it explores it through fiction rather than through a sermon. It delves deep into very bad characters who do terrible things, and strives to show a biblically sound portrayal of how God and the world work, instead of sermonizing it. The book forces the reader through some very uncomfortable experiences, and because of this, it’s been lambasted as being completely unscriptural. I even had someone claim that because Cain didn’t convert in the end, the book was unscriptural, even though the Bible implies he never repented. I also had someone give the prequel, Adam, a negative review saying I made a “dangerous error” by having Adam and Eve sew fig leaves together to hide their nakedness (because that’s totally not written explicitly in Genesis 3:7–hint, it definitely is).

The point I’m trying to make is that I’ve been surprised to learn just how little people really know about the Bible. Biblical illiteracy is epidemic high. And in our world of digital connection, we perpetuate the problem by sharing emotionally stimulating, yet theologically dangerous, content with each other and praising it for its “virtues” (by that we mean how it made us feel). In return, we come to feel we know enough to have the confidence of an expert theologian. We become, “Live, Laugh, Love” theologians, critical of anything that damages our three-point, alliterative theology (I’m referring to the L, L, L of Live Laugh Love).

The end result is that we praise things that should not be praised, we criticize things that should not be criticized, and we create a strange sub-culture where honest artistic expression is misunderstood and maligned while anti-biblical propaganda experiences financial and critical success as “biblical truth.” I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised, because human emotions are a powerful force. And if we’re not daily bowing our emotions to God’s headship, we will consistently choose our emotions over his reality. But I feel protective of author friends and those that I read who make amazing work that goes unnoticed or unappreciated. I’m also creeped out at the possibility that I might, at times, reject uncomfortable truth for a comfortable lie, and hope that we can (as believers) have an open enough community to gently point it out to each other. Hope that makes sense! Great post.

Amen to all of this, brother. Thank you.